Radical Justice: Brianna Ghey and a tale of two mothers

“Extraordinarily unusual.” This was the phrase used by one restorative justice expert to describe

the meeting between two mothers recently. One was the mother of the transgender teenager Brianna Ghey, whose brutal murder last year shocked the UK, and the other was the mother of the girl who killed her. Remarkably, both women resolved to campaign together against the dangers of mobile phone use for children. This is restorative justice in action, a countercultural approach that views violence, community decline and fear-driven reactions as signs of fractured relationships. Instead of seeking revenge, it advocates for restorative approaches to mend the damage caused by conflicts, crimes, and victimisation. It’s a reflection of what the Bible calls shalom; a word that encompasses ideas of universal flourishing, wholeness and delight; a condition of “all-rightness”, of connectedness to each other and to creation. Undoubtedly, taking the restorative justice route is hard. But studies have shown that living in unresolved conflict and nursing our hurts is actually detrimental to our health. Or as Carrie Fisher put it, “Resentment is like drinking a poison and then waiting for the other person to die.” We function at our best when we’re living in shalom, when we’re at peace and reconciled with those around us. Nowhere is shalom more clearly demonstrated than at Easter time, when, as the Bible tells us in Paul’s letter to the Colossians, “all the broken and dislocated pieces of the universe - people and things, animals and atoms - get properly fixed and fit together in vibrant harmonies, all because of Jesus’s death, his blood that poured down from the cross.”

The curious case of the manipulated photograph

The recent Mother’s Day photo manipulation by the Princess of Wales, set against a wider backdrop of fake news and AI-generated media, once again raises the question - how do we know what to trust? Growing up I was told that if I cracked my knuckles I would get arthritis and that walking under a ladder would bring me bad luck. My friend was told that ice cream vans only played music when the seller had run out of ice cream. These claims are fairly easy to test; for example, the American physician Dr. Unger deliberately cracked the knuckles on his left hand every day for 50 years whilst refraining from cracking those on his right to see if he would develop arthritis (spoiler alert: he didn’t). He was awarded an Ig Nobel award for his efforts. The deeper issue with the photo manipulation story though is one of authenticity; if the palace is being untruthful in one area, might it also be untruthful in others? The firm’s credibility is called into question. Growing up I was also told that a man called Jesus died on a cross and came alive again three days later, an event known as the Resurrection. The authenticity of the Christian faith neatly hinges on this one event; indeed, if the Resurrection is merely the first-century equivalent of fake news then the credibility of Jesus, the Bible and Christianity itself is undermined. But if it is true then the consequences are life-changing. Such an audacious claim cries out to be investigated, and with Easter approaching, this might be the perfect time to do so.

What’s behind ‘generation sicknote’?

A record number of 18–24 year-olds are ‘economically inactive’ due to ill health. Some columnists have referred to this trend as ‘Generation Sicknote’, saying ‘snowflakery’ is the issue. Others have been more understanding of their predicament. Not only have this generation come of age during a pandemic but many still live with parents and face dire economic prospects - it’s no wonder they struggle to get out of bed. As with such stories, the picture is complicated and there’s surely truth on both sides; structural injustices need addressing, and more resilience is surely desirable. Though perhaps there’s also something existential lurking behind the trend. Hopelessness and despair are understandable when politics makes you cynical, the climate seems doomed, and you can’t ever imagine being able to get on the property ladder - though meaning and hope are essential to resilience. The Austrian psychiatrist Viktor Frankl was in the WWII concentration camps when he observed that people who had lost hope of a better future very quickly died. Without hope and meaning, we’ll languish. Hope develops purpose and resilience - as the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche put it, ‘He who has a why can get through any how’. This is perhaps one reason why statistically, those with religious convictions and practices generally have better mental health and resilience than those without - they have a ‘why’. The Bible tells a story which gives meaning and purpose to the present, as well as the hope of a better future. This ‘better hope’, which enchants the present moment and points towards a brighter tomorrow, is surely something all of us could do with a bit more of.

AI and the trashing of truth

2024 will be the biggest election year in history, with over four billion people heading to the polls in more than 63 countries. In such a year, seeking the truth couldn’t be more important, though never has it ever been so hard to discern. AI technology is accelerating at breakneck speed, and with it, the ability to create plausible deep fake videos. This creates two obvious challenges to the truth. Firstly, that fakes will be believed, and secondly, that truths won’t be. It's arguably the latter of these that's more concerning. Spreading lies and disinformation is obviously nothing new; propaganda has a long history of mixing lies with the truth. Though when there’s a firehose of falsehoods and fakery, it’d be difficult not to become cynical about everything you see and hear. When people are trained to spot fakes, the collateral damage is a cynicism towards everything. Not only can this information ecosystem challenge democracy, it also frustrates our deepest intuitions and needs. Without truth, we have no compass with which to orient ourselves towards purpose, meaning, and goodness. The Bible has a lot to say on truth; Jesus himself had an especially strong sense of its importance. The truth, he famously promised, will set you free. Somewhere between cynicism and credulity lies an approach to the truth which is too important to give up on, especially in 2024.

Brain implants: a peek into Musk’s imagined future?

Elon Musk’s Neuralink division has successfully implanted its first wireless brain chip into a human, with the aim of healing paralysis and other neurological conditions. Musk is not alone in this endeavour- he's not even ahead of the curve. Jeff Bezos and Bill Gates have already ploughed millions into similar technology, and researchers at Lausanne University have demonstrated that it’s possible for implants to allow a paralysed man to walk again. However, ‘solving’ brain and spinal injuries is just the first step for Neuralink. Musk's longer-term goal is some kind of ‘human/AI symbiosis’, which he described as being of ‘species level importance’. He dreams of new ways of communicating through thought alone - though admits that this sounds increasingly like a Black Mirror episode. The scale of ambition is extraordinary, though we know that Elon Musk is no stranger to big ambition. The question is, if and when practical obstacles are overcome, what kind of world will it create? Less suffering ideally, though the imagined scenarios of dystopian sci-fi also feel plausible. The transhumanist ambition to break our natural limitations is nothing new but is now entering an accelerated phase. To guide this wisely means asking some fundamental questions, some of which have theological roots. Should human value be equated with human capacity? How is this technology changing us as humans? What is the overall purpose of technological progress? How such questions are addressed by the likes of Musk will in some measure determine whether the future will feel like living in a Black Mirror episode.

Sex and porn: are we too easily pleased?

Pope Francis recently spoke on sexual pleasure being a gift from God but warned that pornography undermines it. While teaching on lust, the Pontiff said that looking for "satisfaction without a relationship can generate forms of addiction.” It's not an unexpected Catholic teaching, but one that rewards reflection. The internet is saturated with pornography, the consequences of which are felt by both individuals and communities. The porn industry has turned sex into a lucrative consumer product (at least $15bn a year), treating bodies as sex objects rather than people. Pornography is sadly the first form of sex education that most young people will receive, leading to a legacy of widespread addiction, sexual dysfunction and skewed expectations. A healthy sex life, argues Pope Francis, takes place in the context of a relationship - this is where the gift really comes into its own. Love and connection are often the desire beneath the desire, something which a shallow encounter shorn of meaning can’t possibly deliver. The Pope’s perspective resonates with a point C.S Lewis made last century: “We are half-hearted creatures, fooling about with drink and sex and ambition when infinite joy is offered us, like an ignorant child who wants to go on making mud pies in a slum because he cannot imagine what is meant by the offer of a holiday at the sea. We are far too easily pleased.” There's a difference between arbitrary rules and healthy boundaries. The former seem pointless and mean, the latter are protective and honouring. If it’s true that sex has more than a transactional value, then it makes sense that it's a gift to be given and honoured, not a commodity to be exploited. Though as the Pope also pointed out, “winning against the battle of lust can be a lifelong undertaking.”

Fires, Floods and Fears – how disasters expose our values

What would you try to save if your house was on fire? Over the last few days, we’ve seen striking images of lava oozing through the Icelandic town of Grindavik. Evacuation spared the inhabitants, but the stark reality is cause to reflect on the choices faced by such communities. The images broadcast from Iceland bear an uncanny resemblance to the imagined scenarios of Hollywood film sets. This is no coincidence; apocalyptic cinema is experiencing a resurgence as it taps into our collective fears of climate events and global conflict. On January 24th, Benedict Cumberbatch’s inaugural film production, ‘The End We Start From’ is scheduled for UK release. Adapted from Megan Hunter’s novel, it’s a dystopian cli-fi portraying a mother giving birth as London succumbs to a climate-induced flood, forcing them to seek refuge on higher ground. The story explores the anxieties around motherhood in a perilous world and brings what is of value into sharp relief. Catastrophes - real or imagined - brutally assert the humbling fact that, despite our technology and hubris, so much is beyond our control. The term ‘apocalypse’ derives from a Greek word meaning ‘unveiling’ or ‘revelation’, and aptly captures the essence of these events - they can reveal what we most value and consider sacred. For those of us privileged to live away from disaster zones, apocalyptic films and news stories are a powerful nudge to consider our core values - doing so might help to build a more resilient world in the face of an uncertain future.

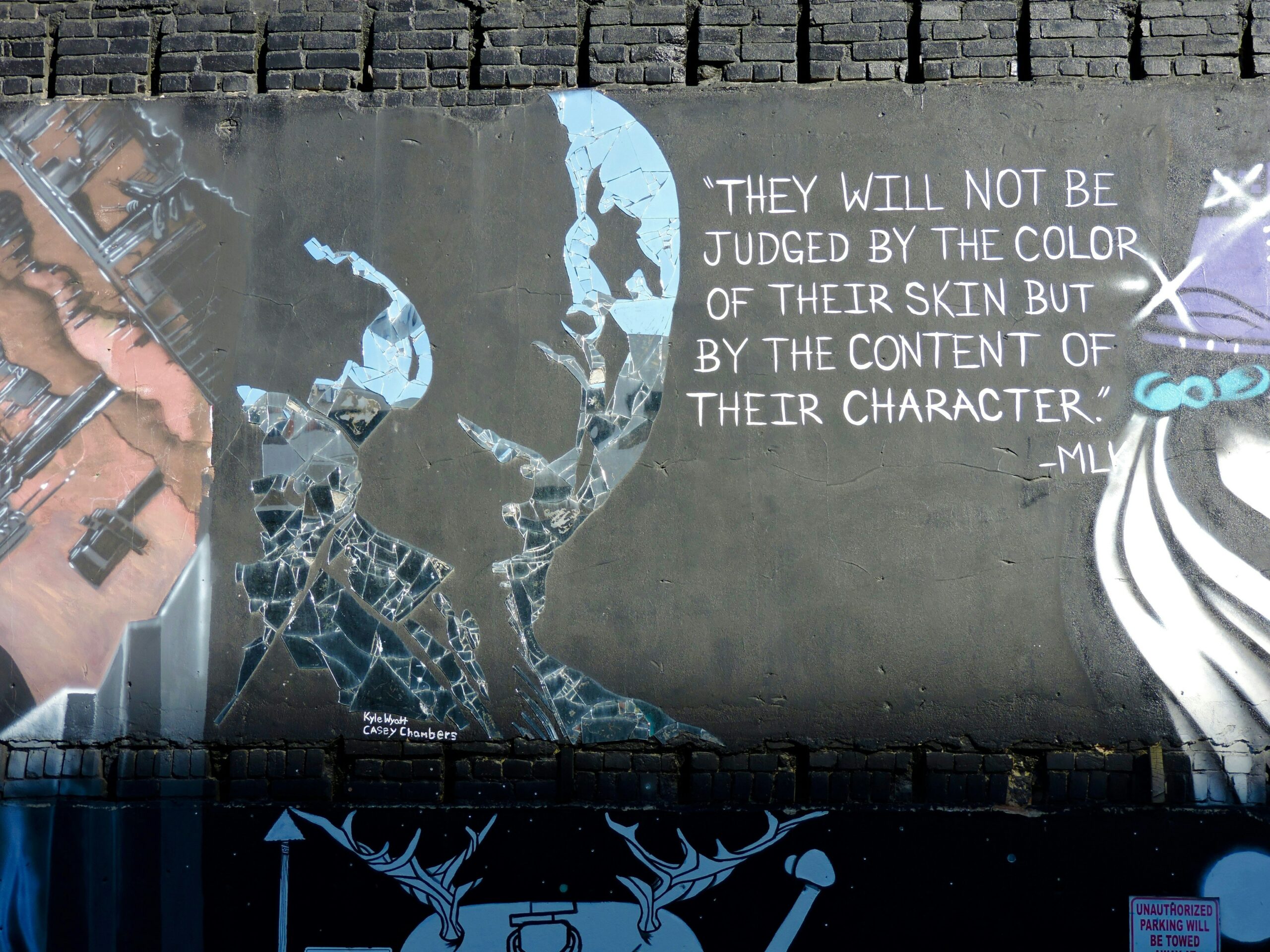

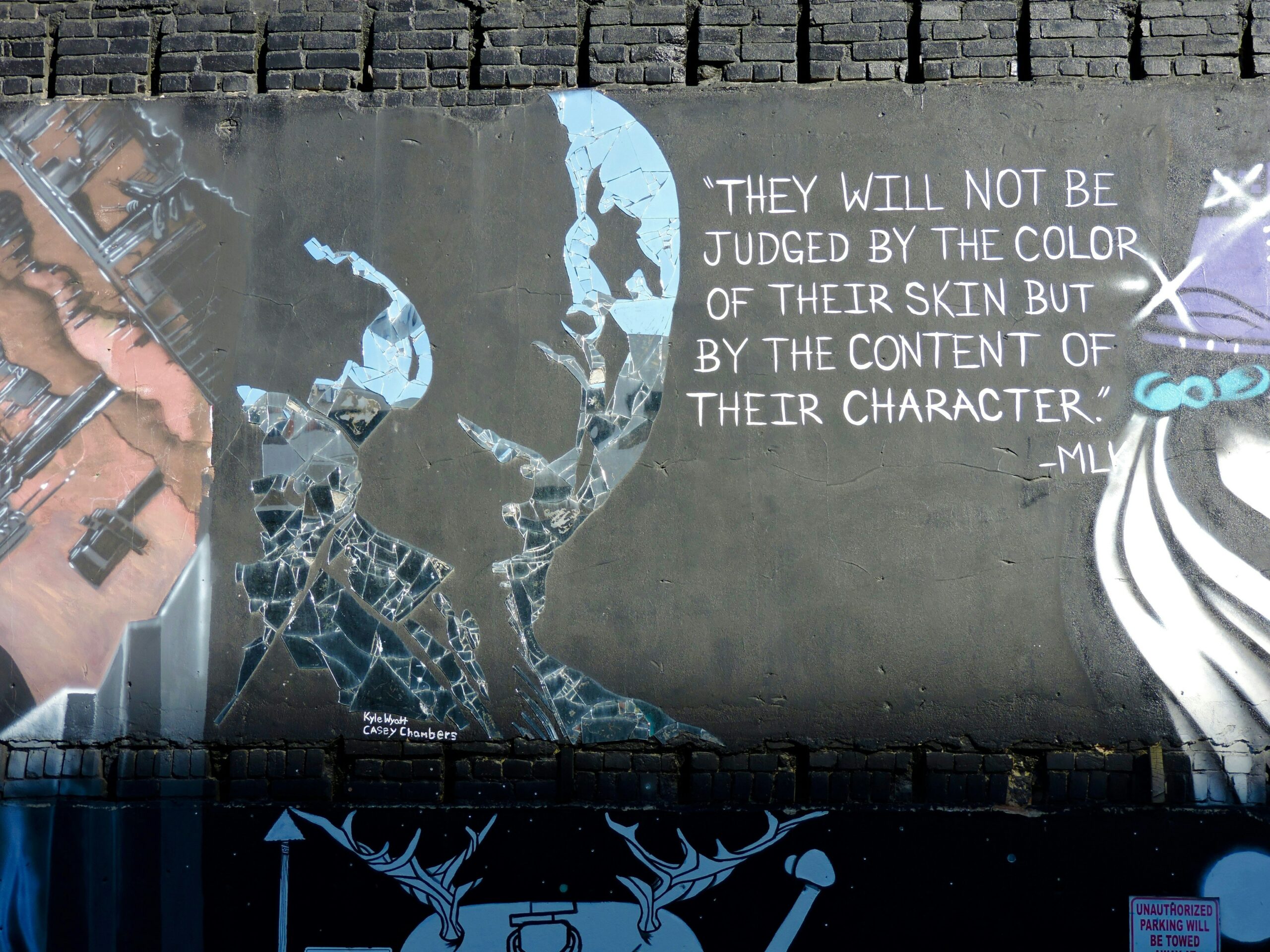

The enduring appeal of Martin Luther King Jr.

The Nobel laureate Martin Luther King is one of the very few people in American History to have a national holiday in his honour. His leadership of the civil rights movement was crucial to the passing of both the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act, throughout which he was committed to a philosophy of non-violent protest. Though amongst his many achievements, perhaps King’s most enduring legacy is to be found in his words. Half a decade or so before King was assassinated, another powerful orator, Winston Churchill, gave a speech commenting that: “Words are the only things which last forever. That is, to my mind, always a wonderful thought. The most durable structures raised in stone by the strength of man...crumble into dust, while the words spoken with fleeting breath...endure not as echoes of the past...but with a force and life as new and strong, and sometimes far stronger than when they were first spoken, and leaping across the gulf of three thousand years, they light the world for us today.” Why do certain phrases and speeches endure across time? It’s surely in part because they express deep and enduring truths. Martin Luther King’s speeches were charged with the themes of justice, interdependence, equality, and freedom for all people - all of which remain profoundly relevant today. While he was a brilliant communicator of these values, he didn’t claim to have invented them. King’s words drip with biblical imagery, and his life was shaped by the Christian belief that these are God’s values. King’s words will continue to echo down through the generations because they carry that same ring of truth that he had found in the Christian message.

Who is the Elf on the Shelf really judging?

The Elf on the Shelf phenomenon is trending on social media once again, as little red elves across the world are hidden by frazzled parents in imaginative and mischievous poses, ready for their children to discover the next morning. It seems these pesky elves have a lot to answer for when it comes to creating - or maintaining - the Christmas magic. The Guardian recently ran a story that found parents are increasingly feeling the pressure to think up new scenarios for their elves, not just to amuse their children but to win kudos among their peers on social media. In these digital tableaus, the elves, initially sent to scrutinise the behaviour of children, unwittingly turn their gaze back onto parents in their pursuit of glory - becoming judges not of the kids but of parents orchestrating their whimsical escapades. Perhaps this irony shades into a broader truth about Christmas, that the season of giving and togetherness can easily succumb to the allure of performance. While Christmas dinner becomes a stage for the virtuoso host, gifts morph into barometers of social standing. Yet buried beneath the customs and expectations of Christmas, the nativity story extends a genuine sense of reprieve from chasing endorsement. The central Christmas story conveys a counternarrative. It tells us that love is God’s free and unconditional gift and that there is nothing we can do- not even forgetting to rearrange an elf- to alter that. For those of us looking for a genuine holiday from the trenches of adult life, surely this is a story where it can be found.

The news at Christmas

Gaza, Ukraine, and Afghanistan are just a few of the headline conflicts where abject misery abounds. Yet even within relatively stable countries, countless individuals and families are facing precarious and challenging circumstances that offer scant reason to rejoice. In what ways does the Christmas festival have anything to say to such situations? The Christmas tropes and trappings that are beamed through screens and shop windows communicate a message of magic, wonder, and human goodness. Whether it’s “Home Alone”, “A Christmas Carol”, or “Miracle on 34th Street”, romantic ideals have shaped the way we’ve come to think of Christmas. Yet the original Christmas story might have more to say to those in despair, than to the charmed and comfortable. In the nativity stories that are played out with tea-towel-clad children and half-remembered lines, some key details from the narrative are lost. Mary, a teenage mother ensnared in the whispers of scandal, and her husband, Joseph, are made homeless because of a political census decreed by a hostile occupation. They are forced to transform a stable into a natal suite, without a midwife or bottle of hand sanitiser in sight. The fledgling family then become refugees, fleeing the edicts of an infanticidal ruler. Governments recess at Christmas, and we tend to think of it as a time to close the doors on the tumult of the outside world. Yet that first Christmas tells the story of God entering a hostile world as a vulnerable baby. It was a world that chimes more with situations in Gaza or Ukraine than it does with saccharine gloss Christmas movies. That first Christmas offered a message to the world - those who feel forlorn and fearful, are exactly the people God chose to dwell with.

You want to have Rizz? Then stop looking for it

‘Rizz’ is the newly crowned Oxford’s Word of the Year for 2023. Defined as the ability to attract a partner through charm, it beat other words such as Swiftie and Situationship to bag the top spot for this year. New words sidle into language because they describe certain cultural preoccupations – Rizz, in particular, was given a boost in popularity among Gen Z when used in a recent interview by Spiderman actor Tom Holland. Rizz contrasts with last year's word of the year ‘Goblin Mode’, a term used to describe a disregard for social expectations and image; surely the antithesis of charm. Like many new words, it was coined and spread largely through social media, which is fitting - social media is where appearances are curated for maximum rizz. While charm may be easily defined, what makes someone charming is more elusive. The English novelist Laurie Lee wrote, “You recognise charm by the feeling you get in its presence. You know who has it”. Lee describes the hallmarks of charm as warmth, sensitivity and ease; those who can charm are, in some sense, social healers. Like love, “it is only given to give away, and the more used, the more there is.” Yet pursuing charm as a character trait is counter-productive, and as Lee also comments, “...it’s deceptive in one thing - like a sense of humour, if you think you’ve got it, you probably haven’t.” Charm (or rizz), flows naturally from its virtuous cousin, humility. Humility, as CS Lewis put it, is not thinking less of yourself, but thinking of yourself less. It’s a virtue the Bible’s book of Ephesians extols. While words will continually evolve, the virtues we find most appealing remain unchanged.

Conflicted priorities: New Zealand’s reversal of Smokefree legislation

New Zealand’s government has announced plans to reverse the legislation introduced by Jacinda Ardern’s government that bans the selling of cigarettes to anyone born after 2008. The Smokefree legislation would cost the government about a billion dollars in tax revenue, a sum which it apparently cannot justify finding from other sources. It’s a controversial move for several reasons, not least the values it exposes. The taxes that furnish the government's coffers are obviously a complicated business. Decisions are influenced by balancing expediency and ideology and should ultimately serve some vision of the common good. While a more liberal attitude to smoking may be justified from a libertarian standpoint, i.e. it’s about maximising personal choice - it’s hard to avoid the sense that this is in no small part a decision to help the economy at the expense of healthcare. Viewed in this light, these plans seem like an implicit reminder that, in this case, at least, economic priorities trump human ones, that present financial concerns trump those of future wellbeing. The NZ government’s decision feels like a case of getting priorities out of whack or, in theological terms - of disordered love. The word ‘decision’ means to 'kill off'; i.e. to opt for one thing means giving up or relegating another. It’s something we do every time we have to prioritise. The decisions we take to prioritise are shaped by what we love; in the words of Jesus, ‘where your treasure is, there your heart will be also’. Perhaps this decision is a glimpse into what the current NZ government considers treasure.

Black Friday, Consumerism, and Finding Fulfilment

Thanksgiving and Black Friday sit beside each other in the calendar, yet the contrast between them couldn’t be more stark. Thanksgiving is a celebration of gratitude which remains relatively untainted by commercialism, yet it transitions seamlessly into the unbridled shopping frenzy of Black Friday; a testament to our insatiable appetite for accumulation. Black Friday is driven by the human impulse to amass and consume; a force that propels economies forward. The desire to buy stuff is, of course, one that is unscrupulously fed and watered by the advertising industry. From gadgets to clothes, to cars, we are implicitly promised easier, better, and more fulfilling lives through our purchases. Who could resist such promises when they are offered to us on Black Friday at such discounted rates? What lures us in is the promise of some kind of salvation; a transaction that promises to make us feel alive and special once again. However there is a paradox inherent to consumerism's design: our acquisitions swiftly become obsolete, leaving us yearning for more. The market, indifferent to our satisfaction, thrives on perpetual desire. On the heels of the aptly named Black Friday, we enter the Christian season of Advent, the prelude to Christmas. While this has also been hijacked by consumerism, for Christians, the festival carries a different story - one that has the narrative power to satisfy the human desire for salvation. It’s a story which subverts the commercial values of Black Friday; salvation is freely available to all, but it didn’t come cheap.

Weathering the storm; what Babet says about the changing climate

Storm Babet, which washed through swathes of the UK last week, has been described as ‘an extraordinary piece of weather’. Communities in different parts of the country saw some rivers rising by more than five metres, leaving those impacted to deal with the detritus and damage of the receding water. Storm Babet might have been remarkable in its intensity, but it was just the latest in a recent salvo of dramatic weather events across the globe, from the bushfires that have raged on several continents to the droughts ravaging sub-Saharan Africa. While these weather events are short-term, their increasing frequency points to a changing climate. There is consensus among climate experts that we should expect more frequent and even more intense weather events in the future. At times, our current climate crisis can feel like its own ‘storm’ with the inevitability of further catastrophic climate events looming over us. The Bible’s book of Romans resonates with this feeling, offering an evocative image that compares creation to the groans of a woman in the pains of labour. It’s a passage which feels like an accurate description of our current climate crisis, and yet, even in the honest acknowledgement of the pain and desperation, the passage highlights an unexpected hope. It goes on to describe the renewal and redemption of the created world. Yet this renewal does not just apply to the outside world, but to humanity itself. Perhaps this promise offers both a challenge and a hope we can learn from when looking to the climate crisis: we may need to look within to bring about change, but we also need a sure foundation that provides hope in the midst of suffering.

100 years of Disney magic

Today marks a century of the Disney company; 100 years of dreaming up enchanted realms, heroes and villains, and stories of the world put to rights. Disney films are characterised by an extraordinary eye for detail. Aesthetically they’re stunning, each with their own style and original soundtrack. Through these imagined worlds and their characters, we’re transported from the every day - particularly appealing at a time when newsfeeds are so saturated with suffering. But perhaps the underlying allure is that Disney films not only show us an enchanted imaginary world, but they’re actually able to re-enchant our own. Great writers like J.R.R Tolkien, C.S Lewis, and G.K Chesterton believed that fairytales draw us in because they speak of reality in refreshing ways. They believed that these stories, with their rivers of wine and purple trees, remind us for one wild moment how extraordinary our own world truly is. They’re also morally instructive: ‘Beauty and the Beast’ tells us that the beast is transformed through being loved. Pinnochio shows us that hedonistic pleasure pursued for its own sake ends in misery. Tolkien suggests that the quality of ‘joy’ we find in fantasy is best explained as a sudden glimpse into the underlying truth of reality. In an era dominated by materialism and relativism, the childlike enchantment we once saw in the world dims. Yet Disney, with its narratives and artistry, rekindles the dwindling spark. It gently nudges us to experience the magic that saturates our world, to perceive again the extraordinary in the ordinary.

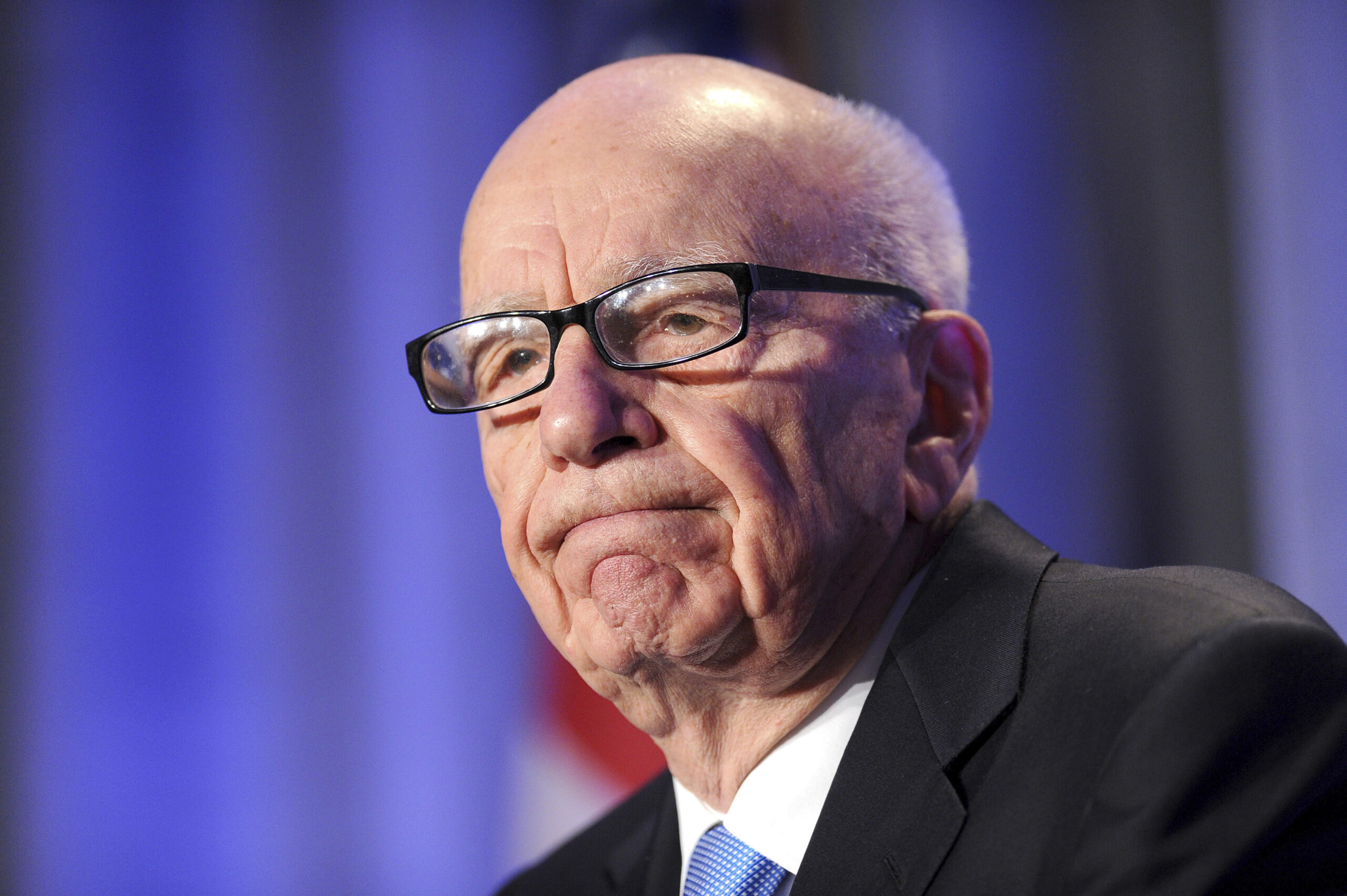

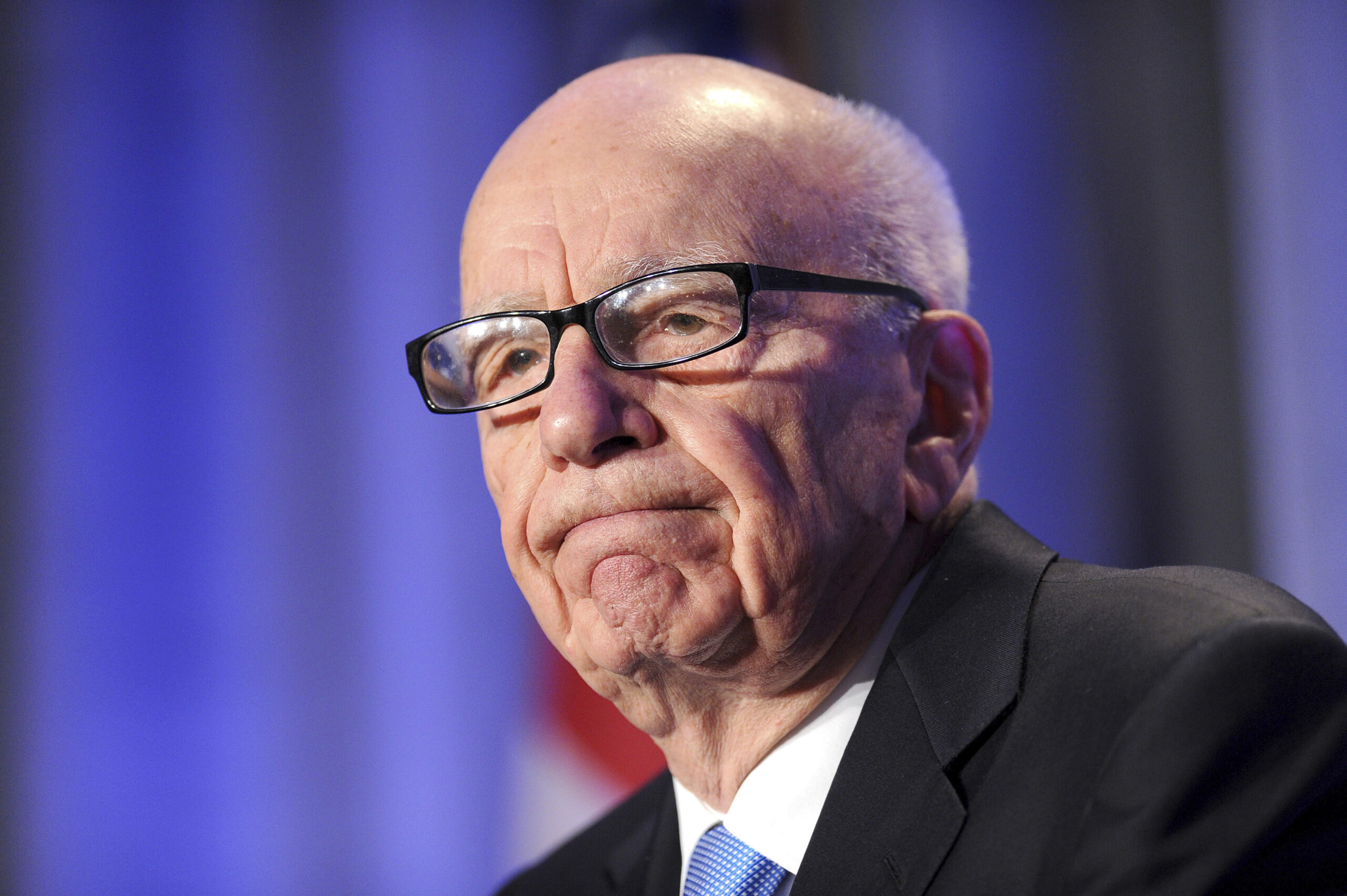

How much of our minds has media mogul Rupert Murdoch shaped?

News outlets around the world are reflecting on the career of 92-year-old media mogul Rupert Murdoch this week, who recently announced that he’d be stepping down as chairman of Fox and News Corp. As the proprietor of hundreds of international newspapers and TV stations, he’s been credited more than any other person in shaping the media landscape in the West- for better and for worse. Murdoch’s press has often been accused of trading responsible journalism for sensationalism; whether it’s unflattering photos of celebrities or scandalous stories of politicians, his empire’s journalistic output has regularly exploited the public appetite for our ignoble ‘love of sweet gossip’, as the Bible’s book of Proverbs puts it. But here’s the thing. We choose our press through our purchasing power. In other words, while the owners and editors might be responsible for the content - the public decides whether there’s a market for it. Jesus said that ‘the eye is the lamp of the body’. What we absorb and take in ultimately shapes the person we become. Whether it’s a story from Murdoch’s media empire or a season we binge on Netflix, each of us ultimately has the last word on what we allow to make an impression on us.

Mind the Gap: What does the felling of the UK’s most iconic tree tell us about meaning and loss?

The felling of England’s famous ‘Sycamore Gap’ tree that stood proudly next to Hadrian’s Wall for almost 300 years has become global news in the last week. It was one of the country’s most photographed vistas, made famous to millions around the world when it appeared in Kevin Costner’s ‘Robin Hood: Prince Of Thieves.’ Its loss has provoked an outpouring of sadness and anger. While the explanation behind such an act of vandalism continues to go unknown, it’s clear no legitimate excuse will be found. On one level, the grief and rage seem relatively disproportionate given the comparatively weak response to the other daily horrors that we take in. Nobody died; nobody was even physically injured. But it’s a scene that has been irrevocably and needlessly changed. Its destruction feels almost nihilistic. Perhaps we can attribute the force of feeling to what it points to – our own inherent fragility and our failure to value the things that matter most. The tree was appreciated, but its presence was taken for granted. We assumed it would always be there. We never imagined a world without it. We all have people in our lives for whom this rings true. Ubiquitous to the human condition is our immutable fragility and our failure to properly value those we claim to love. In the Bible, we read of another Sycamore tree- this time, the scene of an encounter between Jesus and a man named Zaccheus. It was an encounter that led to transformation; to a renewed focus on what really matters. Perhaps out of the destruction of Sycamore Gap, we might also listen for some of the lessons that this sense of loss is expressing.

What does the death of Italy’s ‘last godfather’ tell us about justice?

The “last godfather” of the Sicilian mafia, Matteo Messina Denaro, died on Monday just months after he was captured following 30 years on the run. It’s “the epilogue of an existence lived without remorse or repentance; a painful chapter of the recent history of our nation,” surmised one Italian mayor. Denaro’s life and death bring into sharp focus the various ways that injustice was able to thrive. Not only did he escape punishment until this year and die without any apparent regret, countless others (including businessmen and politicians) who bankrolled and aided him have yet to be identified and brought to account. His life and death highlight a culture of impunity that leaves behind a trail of hopelessness and indignation. This age-old sentiment of injustice has a long history. The Bible’s book of Ecclesiastes finds the author observing: 'I saw something else under the sun: In the place of judgment—wickedness was there, in the place of justice—wickedness was there.' Looking at the world with a moral ledger, we often see that it doesn’t look like the ‘good guys’ are winning. The Bible not only acknowledges this reality, but it makes it clear that despite appearances, there’s more to the story. There is a plot, a purpose, that we're all part of. Justice isn't just a key aspect of this narrative; it's the ultimate resolution and final resting place of it.

What’s in a gift? Inside Kim Jong Un’s explosive party bag from Putin

At the end of Kim Jong Un’s diplomatic visit to Russia, he was gifted body armour and five exploding drones by Vladimir Putin. This particularly unique ‘party bag’ was a brazen public statement of how these leaders view each other, their priorities, and the nations surrounding them. The tradition of state gift-giving is long established, with evidence of the tradition dating back to early Egyptian times. The gift is intended to capture the essence of a nation and is a reminder of the special alliance between the gift giver and receiver. These gifts seem fitting if one’s power and identity come through the barrel of a gun. Indeed, the summit itself was a muscular show of arms, leaving no ambiguity about the priorities of these leaders. Geopolitically, this alliance is worrying and raises questions about the kinds of gifts we would like to see nations giving one another. In 1962, a young Jain Monk named Satish Kumar walked from India to each nuclear power to give leaders a box of ‘peace tea’. The idea was that heads of state would pause and have a cup of tea before doing anything rash. This charming gesture highlights what most individuals and states really want: a state of peace; both the absence of conflict and the presence of wholeness. Two thousand years ago, this was Jesus’ gift to his followers, as he uttered, ‘Peace I give to you, my peace I leave with you.’ It’s an offer that has never lost its appeal and is surely one we could all do with a bit more of today.

How to win at losing

It feels like Christmas for sports fans; the women’s football and netball world cups, the men’s basketball and rugby world cups, another grand slam win for Novak Djokovic, and football seasons (of various varieties) coming to an end in the southern hemisphere and kicking off in the northern hemisphere. I’m a sucker for sporting hype. But a sad thought dawned on me this week; when it comes to watching or playing sport, most of us are losers most of the time. For big leagues and little leagues alike, there’s only one championship cup. Sporting competition always means at least one thing: a whole lot of losers. This might all sound a bit cynical and defeatist. But maybe there’s a lesson in a result that doesn’t end with a trophy. “Sometimes you win and sometimes you learn,” says Robert T. Kiyosaki, author of the bestselling book Rich Dad Poor Dad. Somehow Kiyosaki’s advice reminds me of Jesus’ declaration: ‘At the renewal of all things…many who are first will be last and some who are last will be first.’ Jesus’ words are – of course - more profound than mere encouragement for despairing sports fans. They point to a deeper truth: Success is about more than winning. But to lose well - in sport and in life – we need a conception of reality bigger than the task at hand. We need something beyond defeat on which to set our gaze and focus our hope. If there’s more to life than winning, there must be more to reality than the battles in front of us.

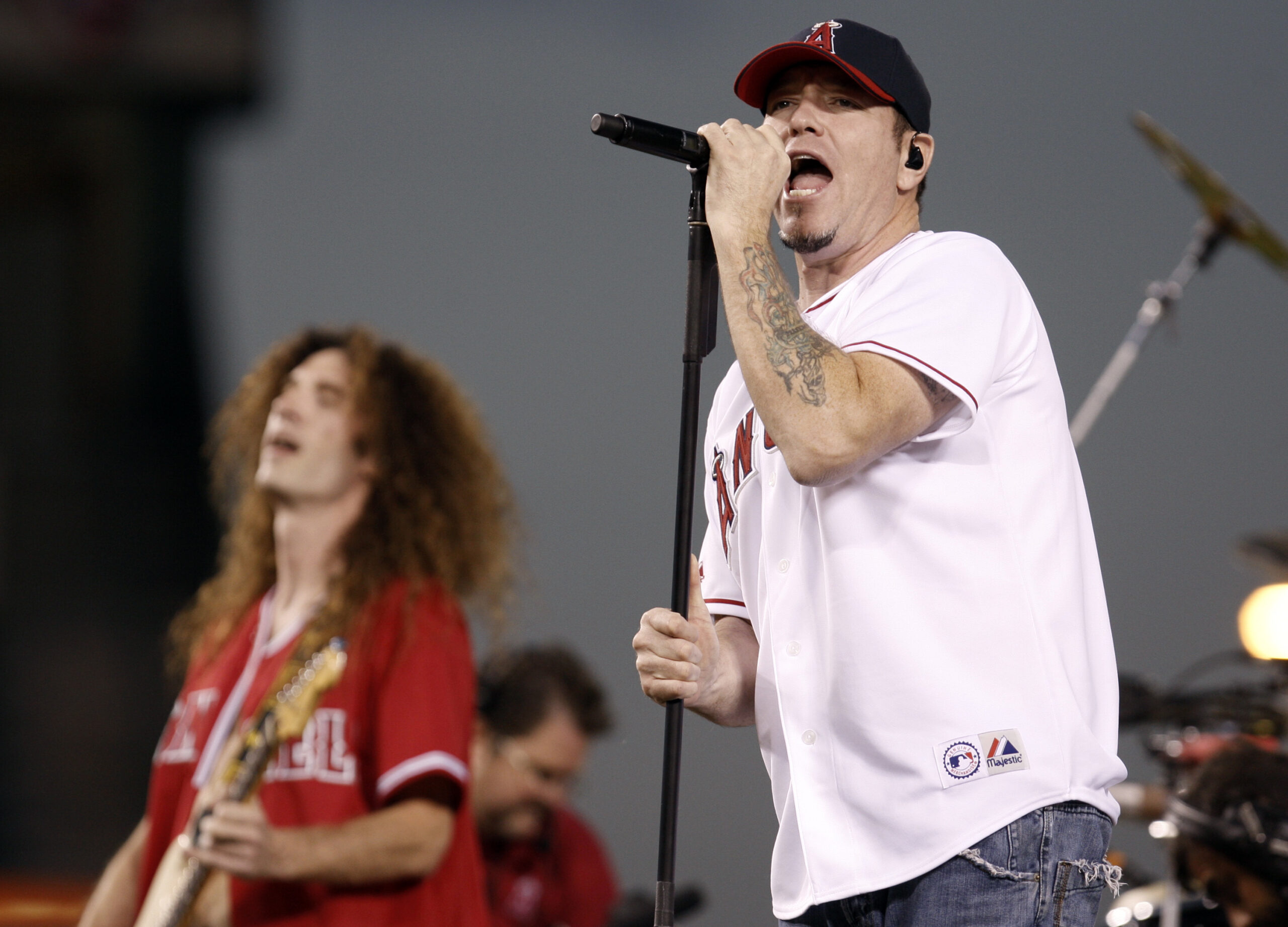

Might as well be walkin’ on the sun…

The death of Steve Harwell, former lead singer of US band Smash Mouth, offers a lesson and a reminder. Those in Generations Z and Alpha may not be as familiar with his music. But for those of us who grew up in the 1990s and early 2000s, songs like ‘All Star,’ ‘Walkin' on the Sun’ and the re-record of ‘I'm a Believer’ (popularised through the Shrek movies), contributed to much of the cultural soundtracks of the day. Smashmouth’s success flowed from its ability to fuse pop, punk, retro and 60s musical stylings, into sticky and happy tunes. However, sadly Harwell’s life was not always as positively energetic as his music. He suffered the unspeakable tragedy of losing his young son to a terrible illness. He battled mental health and alcohol addiction for much of his life. And his death came at the relatively young age of 56. The contrasts of Harwell’s life reflect our reality. Joyful yet broken. Energised yet dejected. Nostalgically cheerful yet painfully sad. We are – at once – caught between some version of elation and dejection. One minute we’re walking on the sun, the next we’re walking through the valley. The Bible recognises this reality. In fact, it diagnoses it. Instead of blind optimism or blunt cynicism, it offers a gritty yet hopeful response. It offers joy and redemption through relationship (with God and with others). It’s a unique combination that can bolster the greatest joys and offer comfort in the darkest valleys.

Why militaries are rubbish at government

When militaries are in charge, things generally don’t go well. This week’s military takeover of the African nation of Gabon is shaping as another example. Militaries have an intended purpose. Ideally, they exist to deter war. Failing that, they exist to fight wars to defend their country. When a military – designed to fight – fancies itself as a government, there are always problems. In the same way that it’s not advisable for a heart surgeon to professionally dabble in what they’re not trained for – plumbing, crane-driving, piloting a fighter jet – militaries serve their countries well when they stay out of the business of governing. Military takeovers tend to violate constitutions, freedom and perhaps most damagingly, ignore the will and consent of the people. The Bible speaks of leadership at its most beautiful, as being anchored in sacrifice and service. There is no military takeover in human history that has honoured these ideals. Gabon’s new leader - millionaire general Brice Nguema – led the President’s security detail. He has now led a coup to overthrow the President. Admittedly, the recently ‘elected’ government of Gabon has questions to answer too. The usual allegations of corruption and media oppression continue to swirl. In these face-offs between power-hungry men, the people always seem to lose. The new leader’s henchmen are welcoming the ‘age of the strongman’ to Gabon. But history tells us that when it comes to building countries, accountability and goodness always do better than raw strength.

Prigozhin headlines: A reminder of human value

The reported death of Yevgeny Prigozhin has been dominating news headlines. His recent ‘almost-coup’ rendered Vladimir Putin the weakest that he has ever been politically. The news reporting also tells us something interesting about the media and the idea of ‘celebrity’. We say that all people are equal but in terms of our attention and our interest, we focus on some lives more than others - Usually for their political influence (like Prigozhin), their relevance to us, their power, their authority, their achievements or perhaps, simply their fame. It’s another reminder that our modern world is built on metrics of value that evaluate people based on achievement, power, wealth, and fame. On one level, this is logical. It’s impractical to expect the news to give every local suburban car accident the same attention as the Prigozhin plane crash. But it’s worth reminding ourselves that a person’s newsworthiness doesn’t determine their value. The apparent death of Yevgeny Prigozhin is of course, newsworthy. But there were others on that plane too. Human souls. Regardless of their political affiliations or their characters, of equal human value. According to the Christian message, people are not just created equal. People are considered – by God – to be masterpieces. Each individual. From the hero to the mercenary, from the prisoner to the postman. God knows each by name. It’s a powerful message that runs counter to our age of power and celebrity. As author J.K Rowling put it: “Every human life is worth the same and worth saving.”

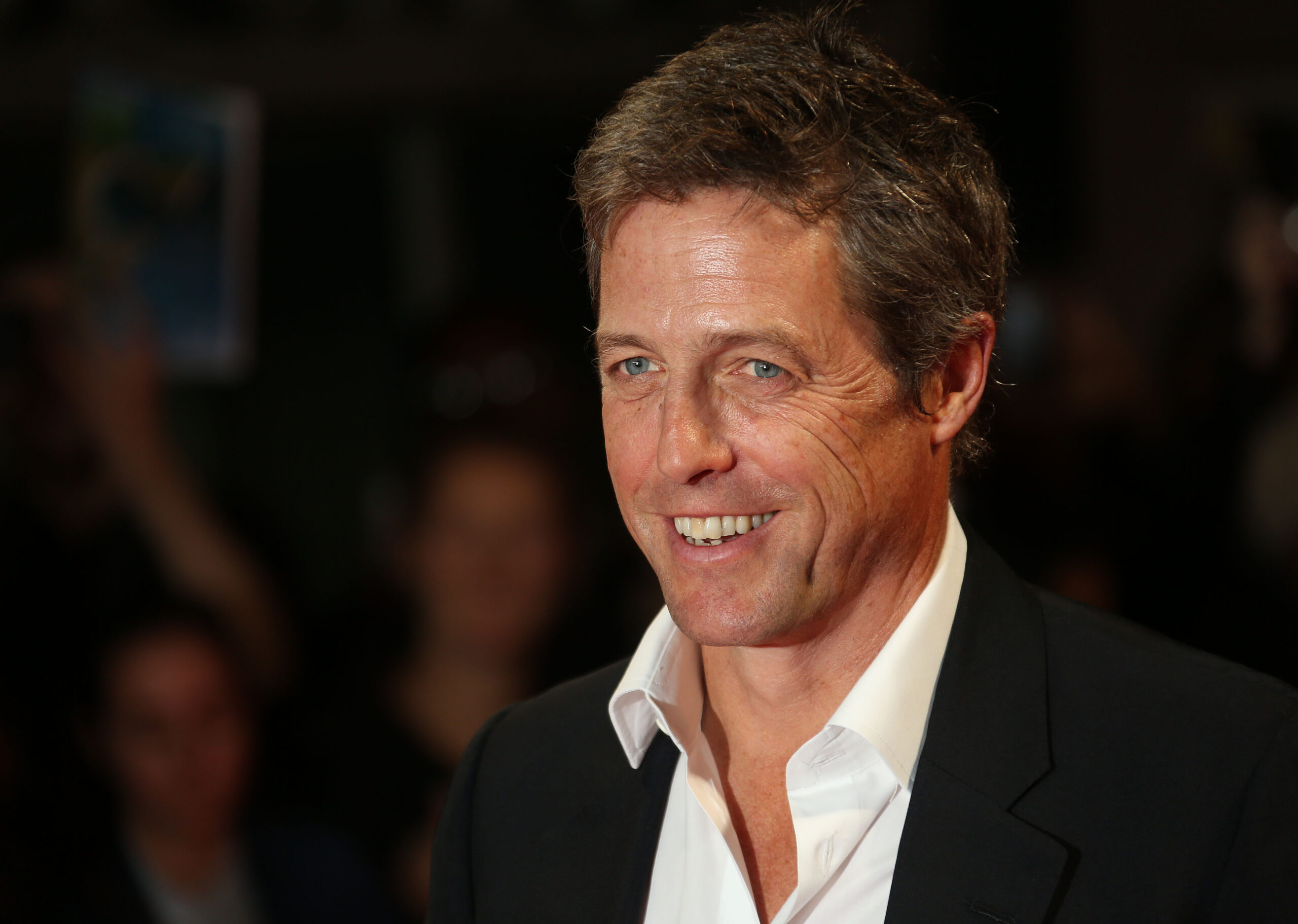

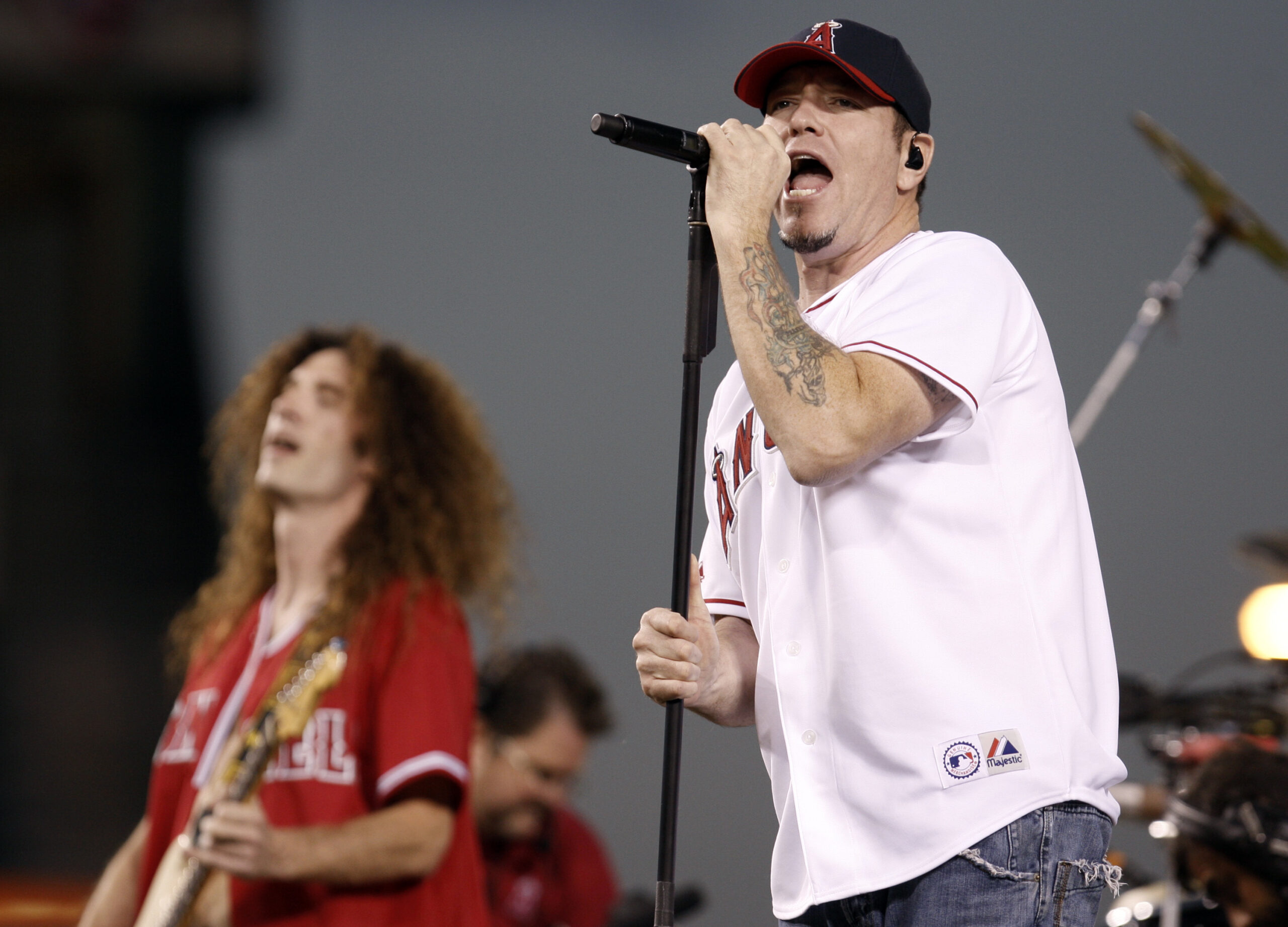

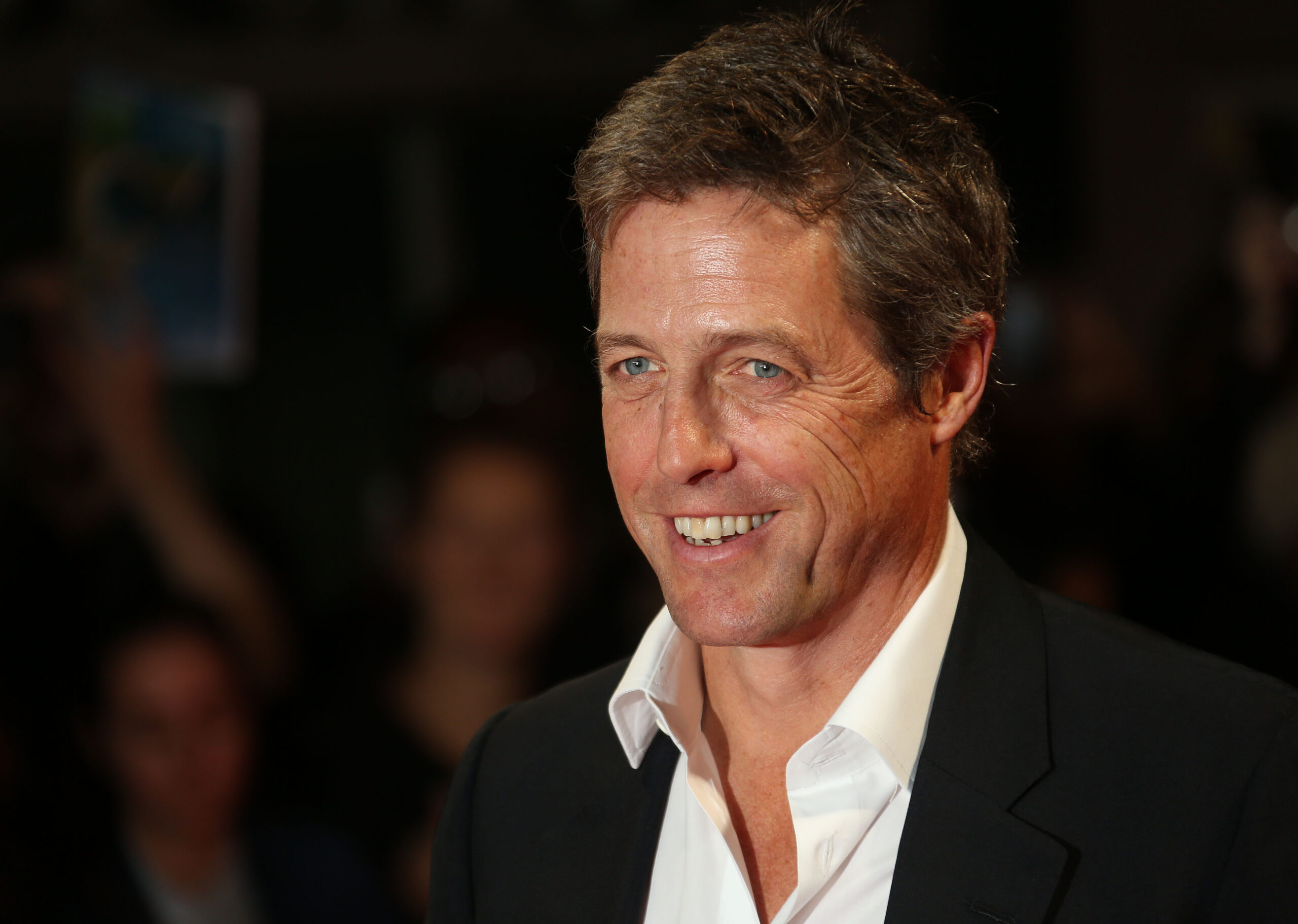

Why Hugh Grant’s wrong about love, actually

Hugh Grant claimed in a recent interview that monogamy in romantic relationships is unnatural. His view is not common, but it’s not rare either. The infamous website Ashley Madison – recently interrogated in a documentary on Disney Plus - is based on the idea that infidelity is not just unavoidable, but healthy. This view assumes that we are all here entirely to follow our short-term desires and to ignore long-term consequences. It puts physical pleasure before holistic flourishing. It puts the self before the other. Where Mr. Grant seems to go wrong is that he thinks of monogamy as a mountain to be climbed. But what if it’s a gift to be given? A journey to grow through? An adventure to be enjoyed? Hugh, it’s about love, actually. The Bible speaks of love as sacrificial, outward-facing and always looking out for the interests of the other. Giving up on monogamy hollows out the concept of love – turning it in on my short-term feelings rather than our long-term flourishing. It takes the focus off ‘we’ and makes it all about ‘me.’ Of course, people can love however they want. But if we hollow out ‘love,’ we lose its transformative, life-giving, and soul-enriching beauty. It goes from being ‘love actually’ to ‘love fictitiously.’ For Love to spread its wings, it needs to be about more than me.

Hawaii fires: Am I my neighbour’s keeper?

Hawaii’s Governor Josh Green has made a plea to people not affected by this week’s horrific fires on the island of Maui to consider taking displaced people into their homes. It’s an important reminder of an ethical principle we can too easily forget. We are responsible for each other, especially in times of suffering. As Dr. Martin Luther King said, the most important question we should ask ourselves is, ‘What are you doing for others?’ When disaster hits at a societal level – fires, floods, pandemics – we instinctively expect our governments to step up. And they should. Part of the reason that we have representative governments (in democracies at least) is to systematise and delegate the services we need, so they are delivered efficiently. It makes more sense for me to pay a little money to my local council to pick up my trash than for me to have to find a way to dispose of it every week. We pay our taxes. We select the governments that we want and they deliver the support and services that we need. Healthcare, education, disaster response, and much more. The risk with this – otherwise logical and efficient – aspect of modernity is that we can forget that though the provision of these needs is delegated (usually through our taxes), the responsibility remains ours. As the Bible says, we are our neighbour’s keeper. I hope Hawaiians take up Governor Green’s invitation to help. And I hope that I always remember that when someone in my community is suffering, it’s my problem.

Andrew Malkinson: When truth and justice become strangers

Miscarriages of justice are a sadly frequent occurrence across the globe. In the UK,

Andrew Malkinson has just had a rape conviction against him overturned, having spent 17 years in prison protesting his innocence. His case highlights a number of alarming issues in the justice system, from the fallibility of identity parades, to the use of

dubious witnesses, the suppression of evidence, and the pressure to confess in order to receive a lighter sentence. The case leaves a burning sense of injustice for both the wrongly accused and the victim, the ‘grave and repeated’ failings of the police, as well as the actual rapist who has never been charged. It's also a sharp reminder of how much the truth really matters. In recent years, we’ve heard terms like ‘alternative facts’ and ‘post truth’ thrown around - though it’s clear that when it comes to justice- when it comes to establishing facts- truth really does count for something. Andrew Malkinson was deemed guilty by the courts, by the public, by the prison officers, and by other inmates. Widely held opinion, however popular and dominant, can be egregiously wrong with catastrophic consequences. For the wheels of justice to turn, truth must be held sacred. Miscarriages of justice like this carry an acutely literal resonance with the words of Jesus, who promises in the Gospel of John that ‘the truth shall set you free’. Where truth is not rigorously sought and appropriately honoured, justice and freedom quickly follow it out the door.

What’s behind the French riots?

The shooting of Nahel M. in the Paris suburb of Nanterre has triggered a wave of violent rioting across France, the scale of which has not been seen since 2005. There’s a long cultural memory of rioting in France from the 19th century. However, as historian David Bell suggests in a recent article for UnHerd, where the 19th-century barricade was a symbol of revolution, today's burnt-out cars mostly represent impotent rage. This simmering rage has been brewing in France’s cites for some time (suburban housing projects hidden from sight); these areas are dominated by communities of immigrants where cultural assimilation has struggled to take hold. Decades of both police violence and police neglect, as well as a sense that racism is baked into much of French society, have stoked a righteous indignation towards the state and its actors - many news stories suggest that these cites have been a tinderbox waiting for a spark. Where previous riots have ultimately won better conditions from the government, some commentators see this wave of riots as backfiring and instead playing into the hands of the growing far-right movement in France. An upsetting sign of this has been the crowdfunding money raised for the police officer who shot Nahel M, which bystander videos show as being a gross abuse of power. France is far from alone in having these issues - the abuse of power and ‘othering’ of minority groups regularly appears in global news cycles. A few weeks ago for World Refugee Day, I suggested that returning to the biblical mandate to treat all people as if they are made in the image of God is the only good foundation to society on; if we expect people to behave humanely, they need to be treated humanely. The riots in France at the moment seem like a sharp example of what happens when we don’t.

Is Putin’s power finally cracking?

Russian President Vladimir Putin experienced an enormous and unprecedented threat to his power this weekend through the uprising of the Wagner Group, a private army of Russian mercenaries. Even though Putin survived, his sense of authority and legitimacy, both in Russia and globally, seems to have been vastly diminished. Interestingly, in Russia's history, this has happened more than once. Russian leaders have sought to gain more power and cement their power by starting wars and starting conflict only to have those conflicts reveal the reality that their powers are actually quite tenuous to begin with. It happened in 1905 when Russia went into Japan and then soon after was overthrown. It happened in the Cold War when Russia went into Afghanistan and soon after the Soviet Union crumbled. And it seems to be happening now with Russia having gone into the Ukraine. Power, it seems, is not something to be grasped for and the more we grasp for it, the less of it we have. Interestingly, this truth is played out in the Bible when Jesus Christ himself, we are told in the book of Philippians, saw his equality with God as something not to be grasped for, not to be striven for. Instead, he gave it away in humility and then it all came back to him. Power, real power, seems to be more about legitimately who we are; the legitimate authenticity of who someone is, rather than the amount of fear and influence that someone can exert on others.

All news is old news

The late British journalist Malcolm Muggeridge said that news is just the same things happening again and again to new people. And we continue to see glimpses of it today; Prince Harry and his wife Meghan caught in a paparazzi car chase, troublingly mirroring the car chase that killed his mother 26 years ago, G7 leaders meeting to talk about the same old things; democratic values, free markets and international rules-based order. And now we see another mini outbreak of the latest variant of Covid; the same things happening again and again. In the Bible’s book of Ecclesiastes, we see this reality of the perpetual, never-ending cycle of history affirmed and made sense of. It tells us there is a time to be born and a time to die, a time to gather and a time to throw away, a time to reap and a time to sew. These cycles are normal; they're not to be railed against or confused by. And while we can't control the cycles, we can control, so the Bible says, how we are and who we are in the midst of them. We are offered, through the Christian message, an identity that is anchored outside of the headlines and outside of the cycles of history; an identity that can give us a sense of resilience and calm and peace in the midst of the uncertainty.

King Charles III: Why does the coronation matter?

The coronation of King Charles III will take place this weekend. Not only will he be crowned monarch of the UK, but also Head of the Church of England. Both traditions are steeped in symbolism. The ceremony may appear to some as archaic in an increasingly diverse and secular society, but the rituals convey messages which transcend both religious and ideological divisions. As Archbishop Justin Welby commented, “It is my prayer that all who share in this service, whether they are of faith or no faith, will find ancient wisdom and new hope that brings inspiration and joy.” Accompanying each investment of power is an attendant symbol of virtue and responsibility. The King will be anointed with oil from Israel in a private part of the ceremony. This ritual, rooted and affirmed in the Bible, is there to set him apart for his role as sovereign. The swords, sceptres, and bracelets he will carry are symbolic of justice, mercy, sincerity, and wisdom. Rituals matter. The King may have temporal power and authority, but the coronation points us to the higher authority from which such virtues are derived. The values and posture woven through the coronation are a timely reminder that where there is earthly power and authority, it must be grounded in responsibility and accountability. It reminds us that rulers are called to embody the virtues of servant leadership. At a time when many world leaders are beset by scandal, perhaps this is the ancient wisdom and new hope the archbishop prays will bring inspiration.

Dominic Raab and the power of humility

UK Deputy Prime Minister Dominic Raab reluctantly resigned last week in the wake of a highly publicised bullying scandal. Part of his defence was that bullying only counts if you know you’re being a bully. But an investigation into his conduct disagreed - it found that the victims' experience mattered more than his intention. Raab’s behaviour had caused “a significant adverse impact on health”, resulting in some of his senior officials going on leave. His perspective was that they had too low a tolerance (or, as another MP candidly put it, were “wet wipes”). But the investigation found otherwise; most of the individuals who made the complaints had many years of experience working closely with senior ministers and they showed “no material lack of resilience”. So what was at issue here? Amidst the debate on high standards, power- and the misuse of it, the extent to which Raab was responsible for the way others reacted to his words and manner was also at play. Clearly there are differences in sensitivity, but if people are going off work because of your management style, there’s a problem. To pull from a recent Economist headline, ‘If enough people think you’re a bad boss, then you are.’ In the Bible, the book of James cautions that we should ‘…be quick to listen, slow to speak and slow to anger.’ These are words which feel especially pertinent to this story, and the premise behind them is one of humility. Cases like this should act like a mirror not just for Dominic Raab, but for ourselves; a sharp reflection of what and how we communicate. The takeaway is not how to get people with a thicker skin. It’s to ask what we’re communicating to others, implicitly and explicitly. Disagreements and discord are to be expected, but to humiliate and dishonour – that’s a choice.

The Kate Forbes debate: Why does intellectual diversity matter?

The Scottish National Party (SNP) leadership contest has been on a steady crescendo since the resignation of First Minister Nicola Sturgeon. The party finds itself split between potential leaders who come from different ends of the ideological spectrum. Kate Forbes has been a particular focus of attention, or more specifically her conservative Christian views on abortion and marriage have been. While she’s stated categorically that she wouldn’t seek to erode any existing freedoms, it seems to be the holding of such opinions that’s problematic. These highly contentious issues are charged with the energy of identity politics, and raise questions about the nature and freedom of public discourse today. The issue lurking behind some of these debates is one of diversity. Thinkers like American social psychologist Jonathan Haidt have made a helpful distinction between diversity of identity and intellectual diversity. The former is rightly championed by most politicians, though the latter appears to be increasingly pushed out of the public square. The censoring of controversial ideas and the creation of ‘safe spaces’ suggests that there are certain ideas that are beyond the pale; they shouldn’t be held, let alone shared. The timbre of the SNP debate in the press is just the latest furore to raise questions about how generous the overton window for intellectual diversity actually is. The pluralist perspective, which once championed a tolerance of perspectives, increasingly appears to be a fragile social contract. While there’s great sensitivity needed when engaging with controversial ideas, there’s equal caution needed if we’re to avoid creating a society where intellectual diversity goes to die.

ChatGPT, What is the best way to rob a bank?

ChatGPT, the new viral chatbot that can hold human-like conversations and turn information into prose in just a few seconds, is continuing to make waves online. Its creation marks an incredible leap forward for AI bots. It even tells you how to rob a bank (although the answer may surprise you). However, as the Canadian academic Marshall McLuhan cautioned last century, with new technology, we must ask not only what it extends— but what it will amputate if it is over-extended. At times impressive, the algorithms ChatGPT uses are often mechanical and lacking in context, nuance, and moral sensitivity. In other words, it's devoid of those human attributes we often need in making decisions and forming opinions. And because the information is swept up from across the web, it can produce text which is inaccurate, biased or discriminatory. The power and elegance of ChatGPT may blind us to these limitations as we cede more of our human functions to a computer programme. Like any technology that promises god-like power, we court the danger of entering a Faustian pact with AI; the more we rely on machines to do our thinking, the less human and humane our world becomes. AI bots like ChatGPT can have incredible reach and power, but it’ll take human wisdom and individual restraint to keep them subdued. Otherwise, as they help us with our jobs, research and bank heists, we could find them robbing us of something far more meaningful. As we watch this new technology shape life and work, perhaps it’s worth considering how much of life we should be trading for speed and convenience. If 21st-century living has taught us anything, it’s that these are very poor values to be seduced by.

Tyre Nichols tragedy: A catalyst for change?

One month on from the fatal beating of Tyre Nichols, calls for justice keep coming. His death erodes yet more trust in the police and screams for a justice system that can be relied upon. But can such tragic events ever be a catalyst for positive change, or do they just make us more cynical? Sadly this isn't the first uniformed abuse of power we have seen recently, not even close. As each new case comes to light and is narrated in the press, the calls for justice are stark. "Heads must roll", as the saying goes, but there is a difference between justice and making things right again. The dead remain dead, and the abused remain abused; each event still occurred, even if someone is appropriately punished. While the wheels of justice might turn, they do not clean the stain or resolve the discord; often, they barely touch the hem of it. In the Bible, we read accounts of violence and injustice. Jesus' death was also at the hands of authorities- there to ensure peace and justice- while bystanders passively looked on. His crucifixion was extreme and without cause. This strange centrepiece of the Christian faith offers relief for those of us who are suffering, who find that God is not peering down from a throne in the heavens but relates to and understands those on the sharp end of injustice. As the English writer, Francis Spufford puts it:“...the most essential thing God does in time, in all of human history, is to be that man in a crowd; a man under arrest, and on his way to our common catastrophe.” The darkness and confusion of these moments are not to be skipped over. Though within the desolation, the story does not end there. In the resurrection, we have the promise of justice and of making things right. The resurrection account of Jesus betokens a world being restored and made new. While we may still live under the shadow of unresolved pain and sadness, this resurrection story contains the promise that it will not always be so. Pain, however raw and visceral, is haunted by the hope of a better world to come. Even though we see only glimpses of renewal, of some wrongs being made right, the story is ultimately one of faith, hope and love- in spite of apparent circumstances. For tragic injustices like Tyre Nichol's death, the Christian faith does not provide soothing cliches for the suffering. Instead, it offers a story that can hold the weight of the moment in its fullness while promising to transform that pain with the hope of a better world. Surely that’s a story worth paying attention to.

What is it about Andrew Tate?

Andrew Tate’s image is that of a wealthy, cigar-smoking playboy surrounded by flashy cars and expensive watches. If the optics sound gauche and dubious, they’re nothing in comparison to his explicit messaging. Tate's extreme and repulsive views, garnering more than 11 billion hits on TikTok, provide compelling clickbait, but what is it about the self-described misogynist that holds so much magnetism for adolescent males? While few condone anything to do with him, many can see that Tate’s success in reaching young men is partly due to a vacuum of role models and guidance. “They want to understand the world around them, and what their place in it is…Our silence is his oxygen, ” says Clint Edwards, in The Independent. Tate offers simplistic narratives to understand the world, and a route to bettering oneself - both of which appeal to confused teenagers. But perhaps it’s more than sense-making and masculinity that draw people to him. It’s the deeper desire for meaning. That, at least, is the hunger he excites. Tate embodies the desire for significance through money, sex, and power. The fast cars and fat cigars, the domineering posture towards women, and the sheer bravado of his persona all tap into primal human urges (particularly in young men). These have been powerful influences on people across space and time; leading Freud to suggest that we're fundamentally driven by sexual desire, and 20th-century psychiatrist Alfred Adler to say that it's a will to meaning that drives human action. We're drawn to money, sex, and power because we think they will fill that existential hunger for meaning. But we'll never have our fill of these things- our appetite for them is infinite. As if to make this point exactly, when business magnate Warren Buffett was asked how much money would be enough, he quipped back, ‘one more dollar’. While they all have a strong lure, money, sex and power are ultimately shallow and unfulfilling places to find meaning. Viennese psychiatrist Victor Frankl suggests that we should look for meaning in aspects of life that are intrinsically satisfying - moral good, spirituality, relationships, and creativity. All of these make the experience of life richer and more meaningful. Andrew Tate appeals because he offers what sounds like meaning to lost teenagers who are hungry for it. But perhaps they need a better story. Perhaps we need to point to those things (with our words and our lives) that provide a ‘better hope’, as the writer in the Bible’s book of Hebrews puts it. If we don’t, then we shouldn’t be surprised when the next violent misogynist starts influencing a lost and hungry youth.

Events that shaped and shook 2022; an invitation amidst the turbulence

The Russia-Ukraine war. More Covid. US-China tensions. Harry and Meghan. Twitter. Spiralling financial markets. Roe vs. Wade. Inflation. Queen Elizabeth II. New prime ministers and presidents… 2022 has delivered its fair share of turbulence and tumult. As per the simplistically insightful remarks of many a sports commentator: “It’s all happening!” And then – like a calm sunrise over a stormy sea – comes Christmas. As ever, right on schedule. With customary suddenness and punctual disregard for the turbulence that precedes it. Our party schedules and shopping lists would have us navigate Christmas as a season. However - according to the Christian message – Christmas is not a season. It’s an invitation. It's an invitation to hope in a world that seems hopeless. An opportunity to reflect in a world of clogged calendars. A cause for celebration in a world beset by suffering. It doesn’t ignore the turbulence of our lives – but invites us to be elevated above it by the astonishing claim that God himself stepped into the world as a person, and now invites each of us into a relationship with Him. There has not been much we could have predicted about 2022, but the unshakeable and unchanging invitation of Christmas is the certain exception to our uncertain world. As we look back on the storm of 2022, this invitation – like a sunrise over a storm – can be ignored or embraced. The choice is ours.

Harry and Meghan and the desire to be heard

As Meghan and Harry release their new Netflix documentary with ‘their side of the story’, former UK Health Secretary Matt Hancock has started releasing his (serialised) perspective on Covid through his ‘Lockdown Diaries’. In this 21st-century media theatre, we can pick out some ancient themes. Righteous indignation (sometimes on all sides), self-justification, and the desire for forgiveness occasionally surfacing (see Matt Hancock on the popular TV show ‘I’m a Celebrity’). Wherever you stand on these people and their issues, one thing seems clear - our perspectives are always partial, always limited. Things are rarely black and white, and can seldom be reduced to a battle of heroes and villains, despite our emotional inclinations to do so. These dramas are very human, with truth and justice often being perceived differently depending on where you’re standing. Whether it’s celebrities and politicians, or our own domestic and workplace feuds; behind each there is the same basic set of desires. A need to be heard, and to be understood. A desire for the truth to come out, and for justice to be done. A need to be forgiven and accepted, despite our flaws and foibles. Perhaps this is part of what keeps drawing people back to the need for stories of redemption. Ones that take seriously justice, truth and the human condition, and find ways of redeeming and resolving the issues that haunt us. The Christian message has provided this narrative for the last few thousand years. In them we find a story that can hold all the elements of a very human drama, but with the possibility of redemption. That is surely a gift that we need this Christmas.

What China’s protests reveal about all of us

China is experiencing the largest and most widespread protests since the Tiananmen Square protests more than 30 years ago. This week's demonstrations raise an interesting question – not only about China – but about all authoritarian approaches to governing people. While the suffering and struggles in our world don’t seem to discriminate based on race or governmental approach, these protests (in arguably the strongest authoritarian government in the world) reflect something undeniable about human instinct – the will to freedom. In recent years, the denigration of free democracies as divided, sloppy, outraged and declining has become a cliché amongst political scientists, commentators and perhaps most gleefully, those who seek to defend authoritarian governments. However, such critiques seem to ignore the jarring clash between authoritarian governments and the human anthropology we all share. One protester in Beijing remarked: “I never thought we’d be able to protest.” The tone of this young man’s comment reminded me of the reaction of a child when they ride a bike for the first time – as if discovering an unrealised capacity and an unknown joy. History seems to teach us that attempts to suppress human freedom – sooner or later – lose out to the deeper instincts of humankind. We can’t seem to help expressing ourselves through our speech, thought and conscience. The Christian message is anchored in such human anthropology – one that is based on the equal freedom and dignity of all people. It is a conception of the person that both history and headlines continue to vindicate.

A Lesson from Malaysia’s New Blue Cheese Government

Malaysia has a newly minted Prime Minister – Anwar Ibrahim - and a newly minted coalition government. For those who are not – like me – shameless political junkies, coalition governments generally happen when no single political party wins enough seats in parliament to control a majority of the total seats. Personally, I find coalition governments frustrating. Like blue cheese, they’re not very popular, they often spark hostile debates, they don’t last long and their blending of political enemies smells strange. That being said, they are a helpful reflection of the challenge we all face: How can we work constructively with people with whom we disagree? The options seem clear. We can shout them down, we can exclude them or we can agree to disagree on some things and work together on other things. Interestingly – and perhaps counter to popular understanding – Jesus did not promise un-thinking unity. In fact, he promised to bring division. He knew something that our post-truth world struggles to accept: Truth binds itself to that which is real and rejects that which is not. Accordingly, debates on what is true will always divide. But that doesn’t need to be a bad thing. According to the Christian message, we should have the freedom to believe what we want, but not all beliefs are equally true. Our challenge is to graciously help each other find truth (through evidence and persuasion), while disagreeing when our convictions demand it, kindly. There will always be divisive debates – on politics, blue cheese, God and everything else– but we always have the option of disagreeing without being disagreeable.

Strange but true- we have more money but we’re poorer

Rishi Sunak is the latest world leader to pass a budget designed to starve off the rising cost of living and an impending recession. But beyond economics, there’s a lot inflation can teach us about ourselves and the world. Supply-driven inflation is when there is less of something, making it more valuable. Our rising energy and food costs are examples of this, due in part to the war in Ukraine and the consequences of standing up to Russia. In contrast, demand-driven inflation is caused by more money in the economy, making that money less valuable. Strange but true – we have more money, but we’re poorer. So our rising cost of living can be boiled down to two things: the fact that we’re standing up for principles and the fact that we have more money. It seems that there's a cost to principles, and more money causes more problems. These two realities point to at least one worthwhile lesson: a myopic focus on the accumulation of wealth is not worth it. The poet Walt Whitman referred to material wealth as ‘conquered fame.’ Jesus Christ warned against gaining the whole world but losing your soul. The phenomenon of inflation seems to affirm both observations. This is not to ignore the impacts of the cost of living crisis. There are vulnerable people who need help and governments should do what they can to bring inflation under control. However, as things settle down (which they eventually will), it’s worth us remembering that inflation (like the value of money) will go up and down over time… … but our principles and identities don’t have to- that is, if we tie them to something beyond the intrinsic instability of our world.